There are always predictions at the start of a new year. Many of them are about new technologies. The Horizon report has a monopoly on this for educaion, using a virtual round table of 'experts' to whittle down all the possibilities into one or two trends that they think will be prevalent in education in the next one year, 2-3 years and 4-5 years. The problem with this approach though, is that you get predictions based on what that small group of experts in really interested in. Predicting the future is fraught with difficulty because the future hasn't happened yet. It's imaginary. But it's on the way...

Imagine if

Darryl F. Zanuck, the famous movie producer, had been on an expert panel in 1946. He remarked: 'Television won't be able to hold on to any market it captures after the first six months. People will soon get tired of staring at a plywood box every night.' So, television was a doomed technology that wouldn't last for long.

What would

Thomas Edison have said if he had been on an expert panel in 1913? This: 'Books will soon be obsolete in public schools. Scholars will be instructed through the eye.' He went on to clarify this prediction: 'It is possible to teach every branch of human knowledge with the motion picture.' Not a bad prediction. It is likely he was correct, but it didn't really turn out that way. People still go to the movies, but it's a special occasion rather than the norm. Most of us watch TV, use the Web to find content, and we still read - whether it is paper based books or e-books, the main question is 'do you like books or do you like reading?' We still read and we still watch. There is room for every technology, all build on each other, and none ever fully supplants.

Even farther back in 1876,

William Orton, then President of the Western Union believed that the newly invented telephone would fail because it had 'too many shortcomings to be seriously considered as a means of communication.' He had a vested interest in promoting mail and telegram services. He was looking at the telephone through his own personal lens.

For what they are worth, my predictions for the future of learning are listed below. Some of you might argue that these are already happening. Yes, they are (and there's the secret of successful prediction!) but they will happen in new and previously unforeseen ways. We will be surprised at how this will occur, and we'll also be amazed at the speed of progress. (NB: remember these are seen through the lens of my own personal interests and experience):

1) Learning will become increasingly personalised. We will have more choice over what we learn, how we learn it, when and where we learn it and over the pace of our learning. MOOCs won't be the end. They are just the start of a huge wave of democratised learning, but that won't stop large corporations trying to muscle in to exploit the surge of interest in 'free content'.

2) Technology will become more embedded in our every day lives. It will be more pervasive, and at the same time it will become less visible, blending into the fabric of our environments (see number 3)

3) We will carry the means of our learning around with us. Our mobile phones (probably the name 'phone' will be replaced by another label - the Germans already call it a Handy) will become cheaper, more powerful and indispensable, and will connect with other technologies seamlessly, probably built into the fabric of our clothes or jewellery (see number 2).

4) Schools will connect more with outside communities and may even blend in with them. They will become places where the entire community can access learning, and where anything can be learnt.

5) Students will generate more of their own knowledge. Formal learning will involve knowledge production as well as knowledge consumption.

6) The 'knowledge experts' as we know know them will assume less importance, because all of us will have the opportunity to become expert in our own specific areas of interest. Teachers, researchers and academics will increasingly become curators and brokers of knowledge rather than simply conveyors.

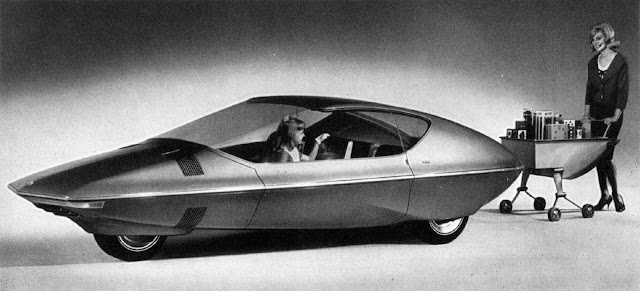

7) Knowledge and skills we have previously taken for granted will become less important to learn. This could be the last generation who will need to learn to drive a car, operate a computer using a keyboard, clean the house or even visit a store to shop for food.

8) We will find new things to do with the extra time at our disposal - it won't all be leisure based though. Instead there will be even more learning to be able to do your job better. It will be just in time, just for me, and just enough learning.

9) Meetings and other work will increasingly be conducted from where you are in the world, using your personal technologies. Many will be visually oriented, and will have haptic and kinaesthetic capabilities.

10) We will all wear spacesuits and live on Mars. (OK, this last one is unrealistic, because we all know that a Mars diet is not the healthiest option - but if the UK government introduces a chocolate tax, I predict I will leave the country).

There are other things I could 'predict', but I've run out of steam (anyone remember that? No? Just me then.) Go on, make up the rest yourself....

Photo by

Mario Klingemann on Flickr

2016 and all that...

by Steve Wheeler was written in Plymouth, England and

is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.