Do teachers have a choice about whether to engage with technology?

Technology is already so embedded in the fabric of schools, it's probably unavoidable now. Whether it's teacher technology, including wordprocessors, electronic record keeping or databases, or student technology, such as laptops, educational software or personal devices, technology should now be viewed as a set of tools that can be harnessed to extend, enhance and enrich the learning experience. Add the exponential power of the Web into the mix, and the argument becomes compelling. Technology offers us unprecedented opportunities to transform education. The question is not whether teachers should engage with technology, but how.

If you had to pick out the single most important technological development for education over the past ten years, what would you choose and why?

The final line of Learning with 'e's offers a clue when I say we literally hold the future of education in our hands. The personal, mobile device has started to transform learning in both formal and informal contexts. Learning in any place and at any time is going to gain traction in the coming years, and the emphasis will be on personal learning. Students can gain access to any amount of resources and connections that will help them to learn; they can use their mobile phones to connect with others; and also create and share their own content with potentially huge audiences outside and beyond the walls of the classroom. The value of this is immeasurable.

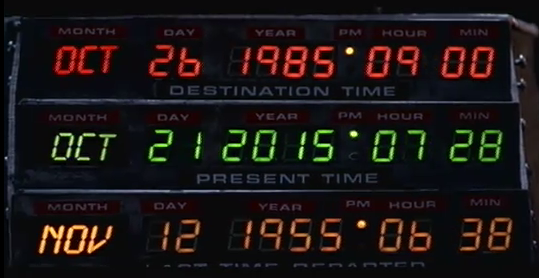

So, you've accidentally invented a time machine, and travelled forward to the year 2115. What do the schools look like?

Communities will always need schools. How education will be conducted, and how teachers will work, is an entirely different question. I foresee a time in the not too distance future when learning spaces will blur their boundaries with the outside world, and where the use of technology to connect schools and people together while they are learning will be paramount. It's already beginning to happen. I believe the boundaries will blur in our roles too, with teachers and students becoming co-learners. The silos of subjects will also open, and trans-curricular learning will emerge - something that will be vital for the economies of the 21st Century and beyond. Children will learn new skills and literacies that will prepare them for a future we can't clearly describe. Technology will play a key role in this preparation, and teachers will remain central to the process. I don't think technology is a threat to future education. It's something we should embrace. Teachers will not be replaced by technology, but teachers who use technology will replace those who don't.

Photo by Jean-Pierre Dalbéra on Flickr

Talking tech by Steve Wheeler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Talking tech by Steve Wheeler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.