This entire week for me seems to have revolved around assessment. I have either been grading assignments, setting assignments or thinking about assessment (I'm speaking at an event on assessment in London later this week). There was even a live #edenchat on Twitter this week about e-assessment, which is archived here. Yesterday I presided over a 2 hour session on assessment with my second year Computing and ICT specialist primary education students. I showed them how assessment is vital - not for awarding grades, but for feeding back to students how well they have done, and what they need to do to improve. This is assessment for learning (AfL) rather than assessment of learning, and it's critical for good pedagogy. What's the difference between formative and summative assessment? I asked. Formative assessment is when the chef tastes the soup. Summative assessment is when the guests taste the soup. You have a lot of scope to change learning, unlearn, relearn in formative contexts. When summative assessment comes along, sadly it is often too late. And that's a problem with final exams and high stakes assessment.

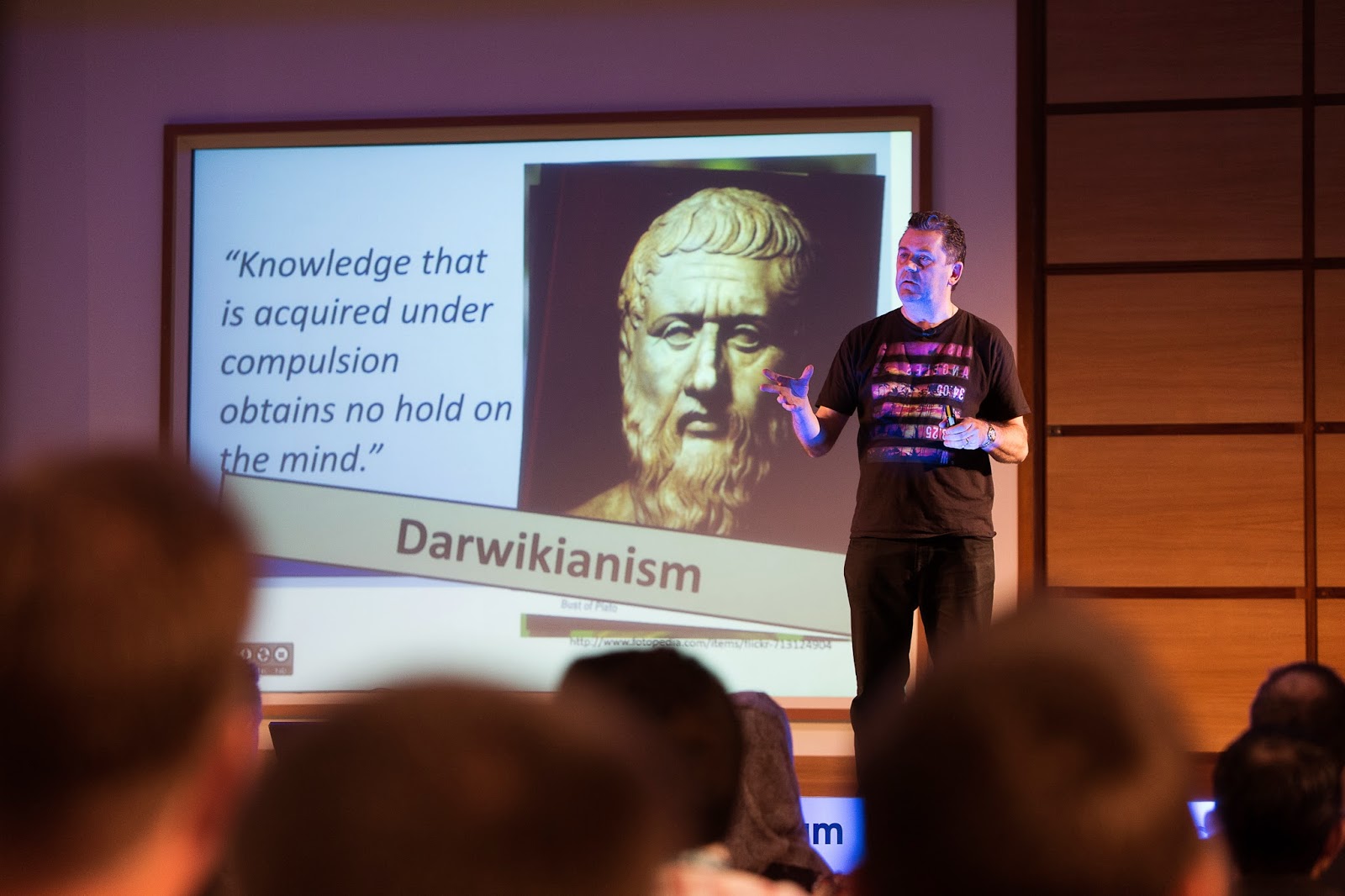

We had a wide ranging discussion about other kinds of assessment (diagnostic, ipsative, triadic, etc), and a deep and meaningful debate about the nature of knowledge. I think we all agreed that in this information rich society, knowledge is changing, and that in some cases 'knowing' itself is taking on new meaning. What does it mean to 'know something' today? In an age where the vast majority of knowledge is discoverable via Google, what happens when kids smuggle wearable technology into the exam room and Google everything? Shouldn't curricula and assessment (especially the high stakes kind) now focus more on unGoogle-able knowledge - the kinds of knowledge and cognitive skills students need to survive and thrive in an information rich world? Testing is far too frequently administered in many schools to be effective and many exams still rely heavily on the testing of fact based learning - essentially the testing of crystallised intelligence. Shouldn't we instead be concentrating on developing young people's fluid intelligence? Does testing serve any other purpose than terrifying children and overburdening teachers? Yes - cynics would argue that it feeds into government league tables and ultimately contributes towards (the leaning tower of) PISA. Should there now be more emphasis on problem solving, team working and collaborative learning? I think we are heading in this direction, but we need to do so more quickly, or we risk losing the hearts and minds an entire generation of learners. Assessment should be primarily about helping students to learn better. It should be AfL. Anything else is mere candy floss.

Photo from Wikimedia Commons by Hariadhi

The AfL truth about assessment by Steve Wheeler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.