To reach the point where they can start establishing a maker culture in their classrooms, teachers often need to undergo a reboot of their mindsets. American educator Jackie Gerstein makes some important observations about how teachers can change their perspectives and embrace maker pedagogy. She suggests that teachers need to break out of their old mindsets, develop new skills and entertain new roles. In her excellent slide deck, Gerstein argues that teachers need to break out of the constraints they impose upon themselves. She provides seven key areas that need to be reappraised around the questions: what does it mean to be a teacher, what is the expectation of teaching, and what might change? (my annotations included)

1. Teachers often believe they should be content experts. This is often a barrier that prevents them from occasionally learning something new from their students.

2. Teachers often believe they should lecture, to directly instruct so they can impart important content to their students. Sometimes this is necessary, but often lecturing is the best way to transfer notes from the teacher's textbook into the student's notebook without having to pass through two minds.

3. Teachers often believe they should know all the answers - but this sometimes precludes further exploration of the topic and the opportunity is then lost for teachers and their students to learn together.

4. Teachers have been trained to believe that there should always be predictable outcomes from a lesson. Sometimes lessons go in a direction that has not been planned, and predictions (aims, outcomes, objectives) are circumvented - teachers should be aware that sometimes, you can't plan for learning.

5. Teachers often believe that a quiet classroom is the best classroom because all students are attending to what they are saying. However, there are occasions when students should be allowed to explore for themselves, create their own content and objects, and where the teacher does not need to be heard.

6. Teachers have been trained to make sure they never make mistakes in front of their students. And yet sometimes, a mistake can become a teachable moment, where everyone - including the teacher - learns an important lesson.

7. Teachers have been told that they should be the sole assessor and evaluator of their students' work. However, self assessment and peer assessment also have important roles in the learning process. Incorporating a variety of alternative assessment methods into the classroom can gain some important benefits.

Jackie Gerstein recommends that all teachers who aim to establish a maker culture in their schools should consider the above points. A change of mindset is the first step, she says, in creating an environment in which students can explore, discover and create and go beyond the sun of the mill, every day learning that occurs in schools across the globe. The outcome is that students interact with each other, external resources, digital materials and content, more than they do with the teacher. They learn to build their own personal communities of learning, and rely more on their own skills and abilities than they do on those of the teacher or content expert. They learn from their own mistakes and express themselves more creatively through their own endeavours.

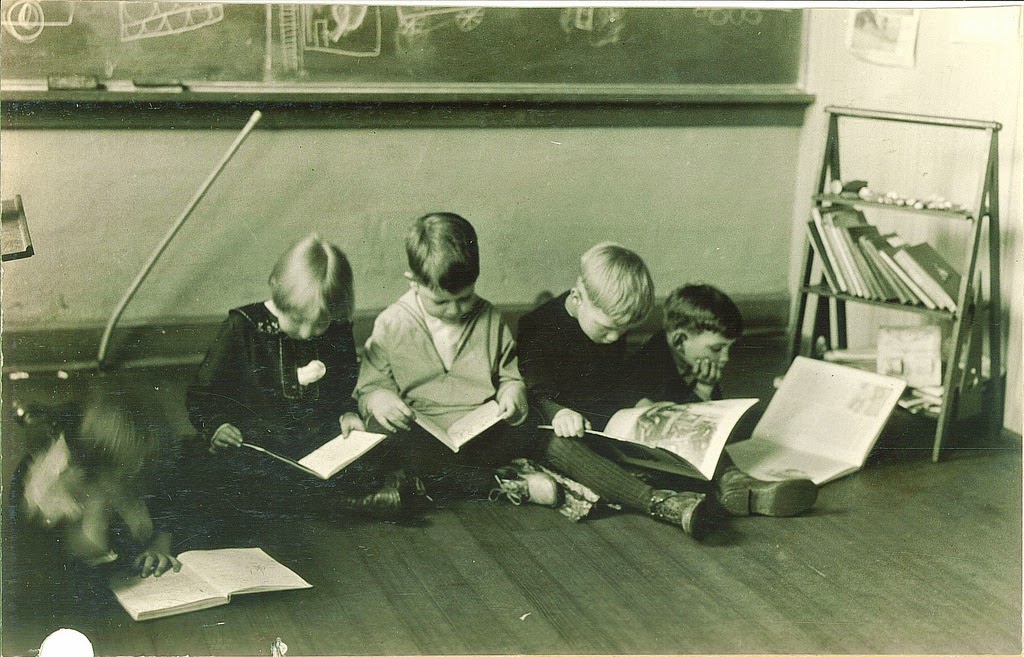

Photo by Pamela Adam on Wikimedia Commons

Maker pedagogy by Steve Wheeler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

.jpg)