In a speech given at Harvard University in 1943, British Prime Minister Sir Winston Churchill famously declared: 'The empires of the future will be empires of the mind.'

70 years on, futurist and physicist Michio Kaku echoes Churchill's sentiments, arguing that intellectual capital is rapidly replacing commodity capital as the most desirable and lucrative means of commerce. Our future will not be built on traditional foundations, but will be different than anything we can imagine. Leading nations will found their success on their ability to develop their intellectual capabilities, and by creating and innovating to solve problems that don't even exist yet.

Kaku warns that it is no longer what lays beneath our feet that is our most valuable commodity. Where once oil, gas, minerals and real estate were the most valuable natural resources a nation could own and trade, now the rapid evolution of technology, economic turmoil and processes of globalisation have privileged intellectual capital above all other commodities. Natural resources run out over time, but the intellectual resources of any nation are constantly being replenished. This is precisely why education is so vitally important. Any nation who fails at providing a state wide world class education system runs the risk of falling behind. In a world where empires of the mind dictate which nations lead economically, socially, politically and culturally, failure to educate a population effectively is courting disaster. Nations who do not understand this they must nurture their education systems will fall into poverty, warns Kaku. I was intrigued whilst visiting Saudi Arabia recently to see that there is now less emphasis on the commodity that made them such a rich a successful nation. The Saudis know that the days of the petrochemical industry are numbered, so they are now turning their attention to trying to develop their education systems into some of the best in the world. Vast construction projects are in evidence everywhere, as the Saudi government pours its money into building new university campuses and research centres, purchasing world class expertise and developing an infrastructure that will harness the potential of learning edge technologies. All across the Middle East, similar projects are also in evidence.

Any nation that roots itself in the past, and fails to prepare for the future is courting economic disaster. Old technology such as telephony has been the subject of radical change in recent years. The old circular dialling interface that was an integral part of every telephone was replaced by buttons and more recently touch screens. And yet many who lived through the transition still talk about 'dialling up' their friends. Such thinking is a remnant of a long gone past, and indicative of a mind set that yearns for yesteryear. It's similar to the way some of our politicians think.

Around the world, governments are attempting to reform their education systems. Leaders everywhere are waking up to notice that traditional, industrial age education systems are lagging behind, that they are deeply flawed and mired in problems that in some cases are intractable. What they may not know though, is that what is needed is not a patch up or a quick revision. In many cases what is needed is a radical rethinking of what education should be. Systems that are not fit for purpose need to be replaced, not repaired. What is required for any nation to succeed is an educational system that is responsive to the needs and demands of its information society, a world where knowledge workers replace production-line workers, and where creative and critical thinking skills are more important than rote learning or following instructions. Schools, colleges and universities simply cannot and will not survive by peddling old ways of teaching in a world where knowledge goes quickly out of date and where new technologies are changing the nature of learning. The empires of the future will truly be empires of the mind, where intellectual capital holds sway. In this respect, we all have a lot of work to do. How is your own education system doing?

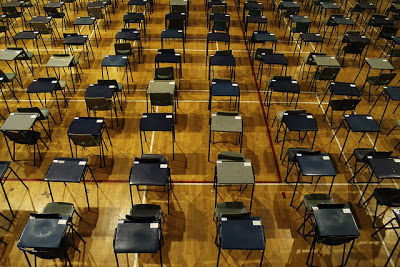

Photo by Robin Kaspar

Empires of the mind by Steve Wheeler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.