The Theory

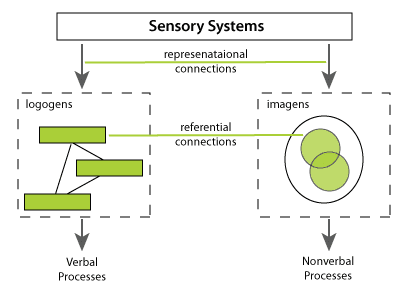

Paivio's dual coding theory considers the way we process verbal and non-verbal information. In 1986 he stated: 'Human cognition is unique in that it has become specialized for dealing simultaneously with language and with nonverbal objects and events. Moreover, the language system is peculiar in that it deals directly with linguistic input and output (in the form of speech or writing) while at the same time serving a symbolic function with respect to nonverbal objects, events, and behaviors. Any representational theory must accommodate this dual functionality.' (p 53). Paivio's model of cognition featured two modes of processing, known as imagens (images) and logogens (words), which are illustrated below.

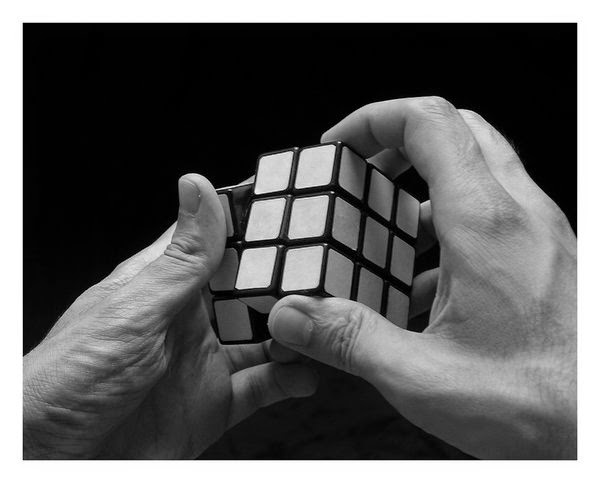

Visual and verbal information are processed in different ways along discrete pathways in the brain, and these are thought to create different mental representations. In a variety of experiments, it was found that people can generally process images faster than text, and can make quicker and smarter decisions when presented with pictures than they can with verbal instructions.

How it can be applied in education

Teachers should be aware that all students can process information in several different ways. Looking at images can evoke a different response to listening to the spoken word, or reading text. Giving children pictures and words in combination can provide them with the best chances to learn concepts. If Paivio's theory is correct, and verbal and image storage of information occur in separate areas of the human brain, then retention (and retrieval) of that information should be stronger (and faster) if both memory traces have been established. The teaching of literacy for example, can be greatly enhanced when children receive verbal, text and imagery based information simultaneously. Thus literacy learning can encompass reading, writing, speaking and listening. Dual Coding theory also explains why multi-media forms of education have been so successful in the past, although alternative cognitive processing theories that feature later in this series challenge this view.

Reference

Paivio, A. (1986) Mental Representations. New York: Oxford University Press.

Previous posts in this series:

1. Anderson ACT-R Cognitive Architecture

2. Argyris Double Loop Learning

3. Bandura Social Learning Theory

4. Bruner Scaffolding Theory

5. Craik and Lockhart Levels of Processing

6. Csíkszentmihályi Flow Theory

7. Dewey Experiential Learning

8. Engeström Activity Theory

9. Ebbinghaus Learning and Forgetting Curves

10. Festinger Social Comparison Theory

11. Festinger Cognitive Dissonance Theory

12. Gardner Multiple Intelligences Theory

13. Gibson Affordances Theory

14. Gregory Visual Perception Hypothesis

15. Hase and Kenyon Heutagogy

16. Hull Drive Reduction Theory

17. Inhelder and Piaget Formal Operations Stage

18. Jung Archetypes and Synchronicity

19. Jahoda Ideal Mental Health

20. Koffka Gestalt theory

21. Köhler Insight learning

22. Kolb Experiential Learning Cycle

23. Knowles Andragogy

24. Lave Situated Learning

25. Lave and Wenger Communities of Practice

26. Maslow Hierarchy of Human Needs

27. Merizow Transformative Learning

28. Milgram Six Degrees of Separation

29. Milgram Obedience to Authority

30. Norman The design of everyday things

31. Papert Constructionism

Photo by Steve Wheeler

Graphic by Instructional Design

In two minds by Steve Wheeler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.