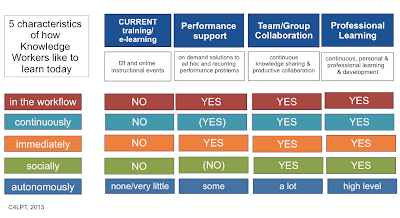

Recently I wrote about

collaborative learning spaces, and argued that we are entering unfamiliar territory. The boundaries of informal and formal spaces have blurred significantly, as have the boundaries between the real and the virtual. It appears that it no longer matters where learning occurs, as long as it is meaningful. Some might argue that learning that is

situated is the most powerful. It is also important that learning is made to be active and engaging. If any of these components is missing, then clearly learning has not been optimised. When children learn, they do so through interaction with others, through observation and practice, discovery and experimentation and by doing and making. All of these aspects of learning are active. When they enter into formal education, they enter into an artificial environment where learning is managed, directed and organised for them. It is not hard to see how such an artificial transition from active to passive can stifle creativity and demotivate learners.

As a response to the problems of learning in homogenised, regimented environments such as classrooms and lecture halls,

Technology Enhanced Active Learning (TEAL) came into being. It is one of several approaches to moving away from tedious and passive learning environments where students are expected to listen, take notes and remember what is being said and presented. TEAL spaces feature several characteristics, including flexible learning spaces where furniture can be moved into many alternative configurations, technology enriched contexts (wireless and untethered, web enabled and personal technologies) and a shift from teacher led lessons to student centred learning, where the learner can take control, and the teacher facilitates. One argument is that simply having access to personalised technologies creates conducive conditions in which active learning can occur. However, the role of the teacher is also paramount in the success of TEAL approaches. Without strategic input from teachers at critical junctures during a lesson, and without some clear goal or set of objectives, students can lose focus, become distracted and go off task.

The idea that students should be able to move freely around the learning space whilst remaining connected is a powerful one. The possibilities of learning through collaboration with other students, and the potential to manage their own pace of learning are also very powerful. Students who can connect to online resources, social spaces and content also have freedom not only to search and discover, but also to create, revise, repurpose and share their own content. A number of psychological and social learning theories can be applied to explain the

transformative potential of this approach. These include the Zone of Proximal Development (Vygotsky) which describes how individual learners can extend the amount they learn when they are connected to other more knowledgeable individuals. The theory of scaffolding (Bruner) also applies where students can gain support for their learning from their peers, their tutors and also through their tools. Social modelling (Bandura) and social comparison (Festinger) may also come into play where learners see the success of other learners and modify their own approaches to optimise the best and most active aspects of their own learning.

Photo by

JISC Infonet

Active learning spaces by

Steve Wheeler is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.