Many of those crammed into the BETT main arena to hear the great man speak were willing to endure the crush, and also the discomfort of standing or perching for over an hour as he held forth on learning, creativity, the role of technology, and the future of education. There were several memorable soundbites, and subsequently a small Twitter storm, as his audience attempted to capture and share the one liners. One of his most memorable one liners was about teachers using technology, where he said: 'The music is in the musician, not the instrument.', and he was also caught channeling Marshall McLuhan with his remark that 'we amplify our tools and then our tools amplify us.'

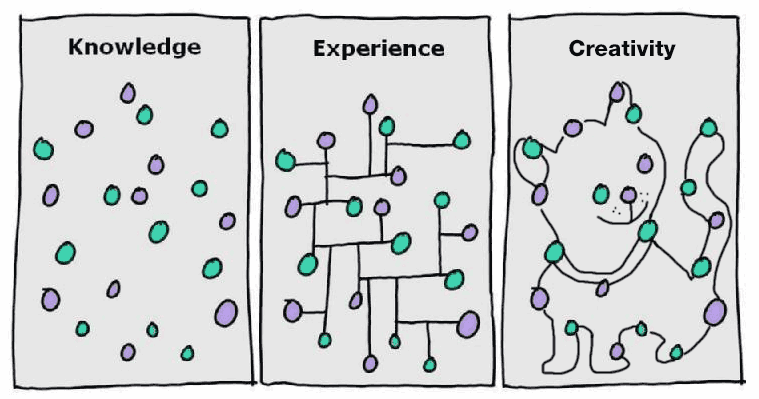

If you can stick around, I would like to spend just a little time deconstructing these sound bites, because I believe they hold a significant message that all teachers should hear. Firstly, the statement that the music is in the musician is profound, because it places all of the emphasis of creativity and all of the responsibility for proper application onto the user. Those who have argued that technology has nuances have a point. The argument is that each technology has affordances - design features that enable the user to perceive their possible applications. However, it is difficult to use this argument to explain the many ways that technology can be used that are not expected by the designers. As Sir Ken reminded us during his BETT keynote, 'people use technology in ways we cannot anticipate.' The design is simply the start of the journey. Thereafter, we can use the tools in any way we see fit.

We need to understand that as we shape our tools, our tools do tend to shape our use of them, but in entering this relationship, we are capable of discovering new and wholly unexpected ways of using them. We discover new tasks and problems that can be undertaken or solved that were previously tedious, mundane or impossible to achieve. This is the beauty of technology. It gives us options. It provides us with alternative approaches and offers us the space to try out new ideas.

When the pianist sits at her instrument, it is used by her to channel her creativity. The music is in her head, and emerges through the dexterity of her hands. The piano becomes an extension of her capabilities, and amplifies her ideas to her audience. Likewise, when the teacher uses his interactive whiteboard, or opens his laptop computer, the prime consideration must be for him to share his knowledge, competence and passion to his students. The key similarity between the musician and the teacher however, is that the musician has her audience, and the teacher has a community of co-learners - all of whom if invited, can join in with the chorus.

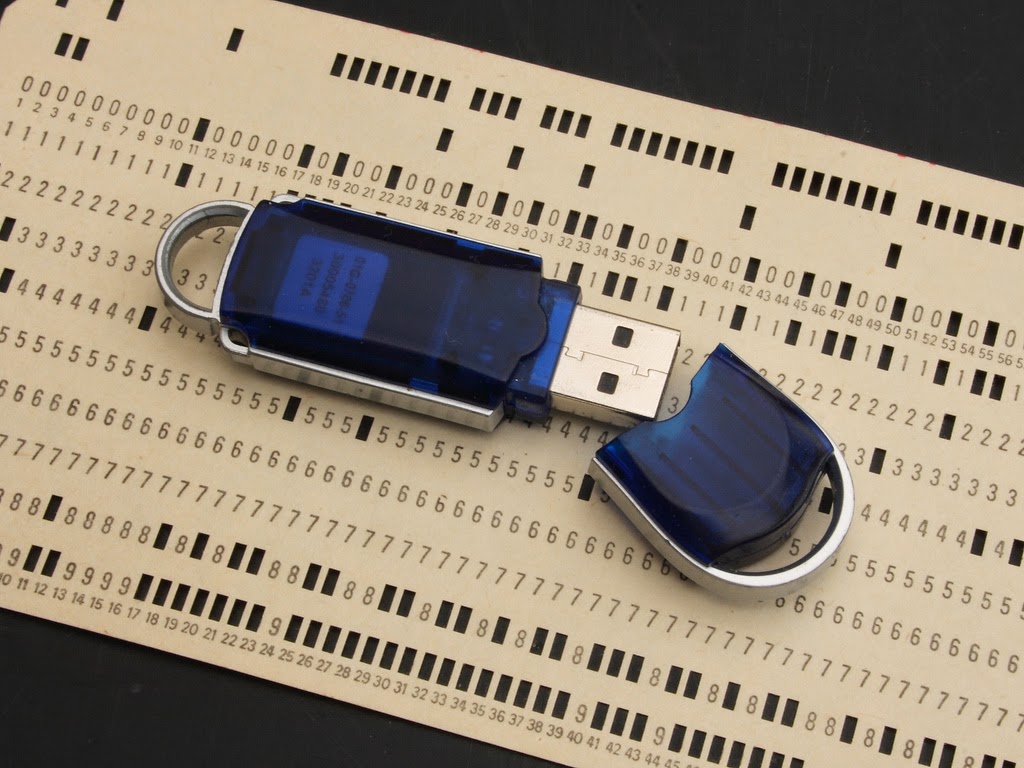

Image by Adam Fowler on Flickr

The music is in the musician by Steve Wheeler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.