|

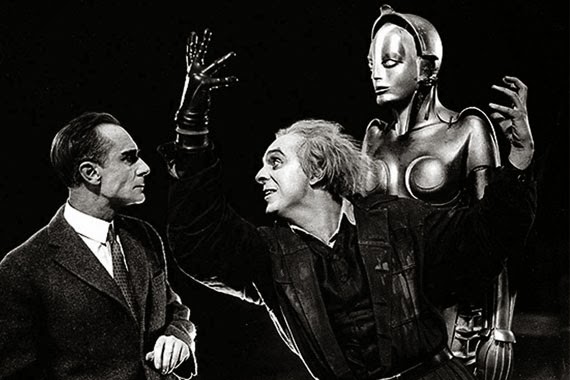

| Scene from Fritz Lang's Metropolis |

Perhaps it was jet-lag and travel weariness that kept Brian fairly quiet over dinner on the eve of Learning Technologies. I noticed that he listened far more than he spoke. Brian Solis is not demonstrative. If anything, he appears quite modest. He doesn't tend to boast over his many achievements. Instead, he simply states it as he sees it. He made his apologies and left dinner early in the evening to get back to his hotel; he then appeared on stage the next morning to present his opening keynote, transformed, vocal, a little larger than life. It was as though a switch had been thrown.

Solis began his keynote energetically, engaging cleverly with his audience of almost 600 delegates from the world of learning, inviting us to share in his fascinating digital musings. He dwelt on organisational use of technology, and presented us with some challenges. He suggested that the future will either happen to us or because of us. In other words, it is up to us to shape our own futures, but our own inability to push forwards is often what holds us back. He argued that technology is a part of the solution but can also be a part of the problem, and unfortunately technology in organisations is usually imposed on us from above. There is no employee ownership, and that is often why technology becomes a problem within organisations, he explained.

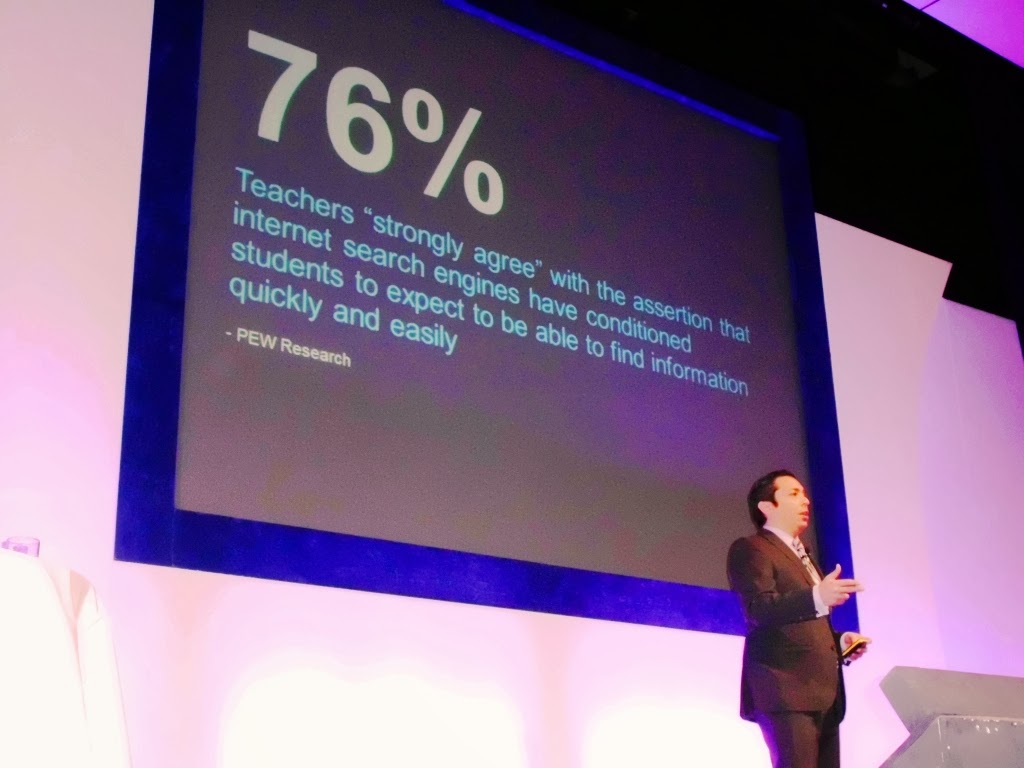

Solis also spent time exploring the use of technology in education. He showed some statistics that reflect teacher attitudes to technology and our knowledge management in the digital age. His slide showing that more than 3 our of every 4 teachers see the Web as a great opportunity rather than a threat, and that it is not fostering bad habits and lazy learning, was positive and encouraging.

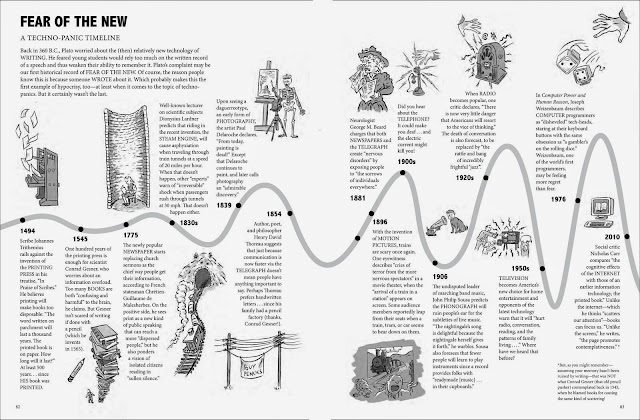

Brian Solis drew on the seminal work of Clayton Christensen, whose model of technology adoption is widely applied in industry. Disruptive innovation, the seemingly uncomfortable process that arises when new technology or ideas are introduced into a conservative environment, is generally unwelcome to many in the business world. We like certainty and abhor change. Yet disruptive innovation is actually an opportunity for creativity and problem solving in organisations, says Solis. When applied correctly, new innovations don't just disrupt the way a company works, they also open up new markets, and change forever the way business is conducted, usually for the best. He listed a number of disruptive innovations that arose out of a need to improve things, including Uber (a disruptive application that manages urban travel), Airbnb (already transforming the travel and holiday industry), Twitter (now not only a social network but also a tool to reflect the pulse of society), Instagram, which has changed the way we take pictures and perceive images, and Bitcoin, which although currently volatile, has immense potential to disrupt worldwide currencies.

We need design thinking if we want to innovate and take control of our futures, was the final message. Innovation, Solis explained, all starts with simple questions. Why do we do things this way? Why can't I do it this way instead? Why doesn't this exist yet? Why isn't this something we do today? These are all elements of design thinking, he added, and these questions can be simplified into four essential tenets:

- Empathy (the why)

- Context (the connected world in which we build)

- Creativity (in the approach to solving problems)

- and Rationality (the logic of testing the rationale and feasibility behind the things we have created).

Metropolis image source

Brian Solis image by Steve Wheeler

Inventing the future by Steve Wheeler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.