If you are immersed in technology mediated communication, there are no apparent barriers to membership of your community of practice. It is your personal network. It is your virtual community. Call it what you wish. To me it resembles a global digital tribe. It is tribal because the global online community exhibits many of the characteristics of traditional, territorial tribal practice. Whether or not we realise it, if we regularly use social media, we are members of the world wide digital tribe. Most anthropologists agree that a tribe is a (small) society that practices its own customs and culture, and that these define the tribe. Tribal identity in the age of the Web transcends ethnicity, traditional cultural expectations and geography (Wheeler, 2009). The global digital tribe has many smaller sub-sets we can call clans. These often exhibit customs and cultural values that separate them from activities that occur in 'real life' contexts. It would be ridiculous for example to

'poke' people in real life. People feel free to say much more on Twitter than they would dare to say to someone face to face.

There is a history behind this.

Industrial society eroded the tribal gatherings of more primitive societies and redefined community. Vestiges of ancient tribal culture were often preserved only in large gatherings at public events such as football matches (where two opposing clans were likely to clash), and in smaller community gatherings seen for example in the ritualistic gatherings in the local pub or at a church service.

Post-industrial society saw the emergence of personal computers, the Web and a global communication network of mobile phones. Social media, the most social of all modern technologies, provided us with shared virtual spaces where we could 'meet'. We now regularly find ourselves gathered around digital totems, where we tell our stories, give our warnings, share our ideas. We celebrate, commiserate and collaborate, and the digital totems we gather around are the virtual clannish spaces that facilitate these actions. We have, it seems come full circle, and 'community' has once again been redefined.

Facebook is currently the largest of the digital totems in the social media universe. The Facebook clan (a sub-set of the global digital tribe) attracts in excess of one billion tribal members, many of whom are busy telling their stories, celebrating success, sharing images and videos, showing their allegiance to their idols (liking a pop star page or a movie premier), playing social games and engaging in frivolous behaviour. There are many other smaller digital totems to choose from. One is the Flickrite clan, who gather to view and discuss photographs. Another is the Wikipedian clan, which exists to create knowledge. Yet another is the

Google Hangouts clan, whose totem has a number of affordances to support all of the above tribal activities as well as the collaborative sharing of spaces, and video linking for synchronous communication that overcome physical constraints such as geographical distance. These are probably some of the richest digital totems in terms of their media communication capabilities, but there are many others, some global, some regional versions, some specific to particular languages, some aligned to particular interest groups or age ranges. Digital mediation and connection are becoming a societal norm for many in the Western industrialised world, transcending time and space constraints, providing communities with their social glue.

I once wrote:

"Where digital communication has fractured the tyranny of distance and computers have become pervasive and ubiquitous, identification through digital mediation has become the new cultural capital" (Wheeler 2009, p 68).

By this I meant that each individual who habituates into regular use of digital media enters into membership of their particular digital clans. We begin to identity ourselves through the relationships we have developed with others during the time we spend around our digital totems. Some we know in real life, others we only know through the digital connection. Either way, we tend to go where our friends are, and that changes over time. Membership of digital clans can be volatile, as has been demonstrated in the sharp rise and decline of once popular tribal online spaces such as Bebo or MySpace.

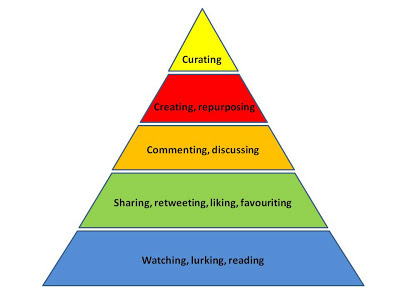

Whereas in real life space, we connect with each other through commonalities such as interest, age or gender ethnic similarities, and identify with like-minded others through our body language (postural echo) and clothing (costume echo), in tribal digital spaces, we express our affinity and interest by liking, favouriting, retweeting, poking, following and tagging. These are visible expressions of friendship and belonging that amplify their presence across the connected tribe, in a similar way that drumming, dancing and story telling have always been the cultural capital of tribal life around traditional totems. Internet

memes - units of digital cultural knowledge - are very easily propagated and amplified across social media platforms. The transmission of such memes can become viral, with exponential spread of content, often initiated by the desire to share interesting content with the members of one's community. Such activities could be construed in the tribal context as 'marking of territory', or expression of ownership over artefacts (Wheeler and Keegan, 2009).

How can we harness the power of these tribal characteristics in organisational learning? Many of our digital tribal activities are performed on an informal basis. People use Facebook or Twitter because they want to, not because there is an organisational requirement. It is a strange conundrum that most organisational learning that is presented in digital format is delivered through

Learning Management Systems (LMS) - many of which are so poorly designed or difficult to navigate that employees and students tend to avoid using them. My students tell me they use the LMS when they have to, but they use Facebook when they want to, because their tribe meets there. The tension between formal and informal learning sometimes can be reduced to such prosaic choices such as this.

Organisations should beware of silencing the voice of the individual. Many tribes

'embrace the status quo and drown out any tribe member who dares to question authority and the accepted order' (Godin, 2008, p 4). Social media tools offer members of the tribe, even a tribe as large as a multi-national company, the means with which to make their individual voices heard above the cacophony of daily working. Blogs, video sharing and other personalised technologies can enable anyone to contribute to the discourse.

Another thing we need to acknowledge is that a lot of learning is social. Employers need to see the opportunities that social media can present for employees to engage socially, wherever they are located. Further, because people learn from each other informally, informal meeting spaces should be seen as vital to the learning process, rather than undesirable distractions that need to be eradicated from the workplace. The most familiar social space, particularly for distributed work teams, is the social network. Next, learning and development leaders need to realise that not all learning can or should be provided from central sources. Increasingly, tacit forms of knowledge are important, and this can often best be acquired within the tribal community. Finally, learning should be situated. The best learning is acquired within the same spaces in which it will later be applied. For knowledge workers in particular, the place where learning will be applied is invariably online, in amongst the shared virtual spaces, and around the totems of the global digital tribe.

References

Godin, S. (2008)

Tribes: We need you to lead us. London: Piatkus.

Wheeler, S. (2009) Digital tribes, virtual clans. In S. Wheeler (Ed.)

Connected Minds, Emerging Cultures: Cybercultures in Online Learning. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Wheeler, S. and Keegan, H. (2009) Imagined worlds, emerging cultures. In S. Wheeler (Ed.)

Connected Minds, Emerging Cultures: Cybercultures in Online Learning. Charlotte, NC: Information Age.

Photo from

Wikimedia Commons

Global digital tribe by

Steve Wheeler is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.