Professor Terry Anderson, who is based at Athabasca University in Canada, is one of the famous figures of contemporary education, and his list of achievements is lengthy.

He is one of the pioneers of online and distance learning, and currently serves as the editor of the influential online open access journal International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning (

IRRODL).

His work around the study of social and cognitive presence in distance learning contexts has been cited many times, and his research has led to a number of high profile keynote speech invitations around the globe.

We are delighted that Terry will be delivering a keynote speech at this year's European Distance and E-Learning Network (EDEN) Conference in Zagreb in June. I managed to grab some of his time to ask him a few questions about his work.

Steve: Thank you for agreeing to take the time out of your busy schedule for this interview, Terry. My first question is how did you start? When did you first become involved with research into distance education and online learning?

Terry: I was first attracted to distance education as a student. I lived as a “back to the land” farmer, woodworker and later a teacher, on a farm in Northern Alberta in Canada. I used distance education courses to complete a Masters degree and soon was involved in distance education delivery for a local community college. Providing access was then and still remains my biggest motivation. Now of course access means time and place shifting for distance education students who mostly live in large cities. However, education is too important to be left to those who can attend expensive campuses. I later was the first director of Contact North, a multi-institutional delivery network in Northern Ontario. As I got deeper into distance education administration, I realized how little I knew about research and the historical and theoretical background of our discipline. Thus, I eventually enrolled in a PhD program studying with Randy Garrison and I guess I’ve been at distance education research, publication and practice ever since.

Steve: Your work has been an inspiration to others in education, but what inspires you the most about your own work?

Terry: I love the freedom of being an academic and the opportunity and challenge to being a teacher. Being an Academic has allowed me to travel widely, to meet some very interesting people and to set my own research agenda. Being a graduate school teacher allows me to interact with some very dedicated students and play a small part in helping them undertake important projects. In the meantime, like most professors, I like to talk (sometimes too much!) with students and share my ideas.

Steve: What is the most interesting educational innovation you are currently aware of?

Terry: Of course the proliferation of web 2.0 tools or user generated content tools are very exciting and I think promise to greatly enhance distance teaching and learning. Education always has been more than information dissemination or publishing, but now we have the tools, at low costs and globally available to make participatory learning possible. I’m especially interested in social media that can be used to go beyond the often institutional centric LMS systems. However, I’m not so thrilled about moving directly to commercial systems like Facebook or LinkedIn, due to privacy and ownership concerns. Thus my colleague Jon Dron and I have been building an Elgg-based open access social media system at Athabasca University that offers much more student control, ownership and persistence to create learning “beyond the course”.

Steve: You wrote a book recently with Olaf Zawacki-Richter - what are the main themes of this volume?

Terry: The book, Online Distance Education - Towards a Research Agenda will be published by the time of the EDEN conference. Olaf had the idea to create a summary reference for the major research issues that we struggle with, research and write about in distance education. He had done a fairly extensive study that extracted the 15 major research themes from the major international, peer reviewed journals in distance education. Using Google Scholar and our own networks, we identified and invited the “grandest of the grand gurus” who have researched and published in each of these areas and invited them to summarize that issue, identify theories and practices related to that issue and suggest further research. We were pleased at the response and after a few rounds of editing, more rounds of editorial and peer review by our publisher, we had 15 chapters and over 400 pages of what we think is very high quality text. We also wanted to find an open access publisher. Thus, the complete book and individual chapters will be available in paper format (for a fee) and in PDF format (for free). The book is part of the Athabasca University Press Issues in Distance Education series and available

here.

Steve: Your interest in online research is well known. What are the major challenges with this approach?

Terry: I almost hate to say it but one of our biggest challenges in distance education research, is distance between the researchers! Unlike most research centres, even those at Open Universities, at Athabasca our faculty work from home offices and we may never meet our graduate students face-to-face. I suppose we could be better at it, but the lack of researchers and funding to employ full time assistants who can take time from their busy lives and employment is a continuing challenge. Beyond that much of what happens in distance education is cloaked behind passwords and in private studies, thus a researcher has to find ways to assess teaching and learning - and sitting in the back of the classroom and conducting face-to-face observations, measurements and interviews is challenging. Finally in my own work, I try to combine research with active innovation. Despite the promise of change in many of our distance education mission statements, like all institutions of formal education, we have trouble adapting and innovating in times of rapid social and technological change.

Steve: What would be the three most important things an educator would need to know today?

Terry: I think like any professional, distance educators need to know how to effectively use the tools of their trade. This is challenging for distance educators specifically and educators generally because the types, variety and capacity of these tools are under going very rapid change. Thus, ongoing levels of media and specifically network literacy are critically important. Second,to follow from Marshall McLuhan the Medium is the Pedagogy (first coined by Cousin (2005). New tools give rise to new ways to teach and learn and these are guided by our understanding of teaching and learning pedagogy. Thus, educators need to experiment with new pedagogies and see how older approaches to teaching can be adopted to take advantage of the affordances of new media.

Finally, getting our heads around new organizational models including the role of for-profit companies, efforts to massif or expand current models to scale and efforts by neo-liberal forces to commercialize and profitize public education present real challenge for us.

Steve: Massive Open Online Courses are currently a major focus of attention for academic, corporates and even governments, and indeed have been covered extensively by the media recently. What are your views on MOOCs?

Terry: I generally support the efforts to scale education, as we have always done in distance education. I think that students, by and large, have been denied much of a “digital dividend” that they deserve. At least in North American tuition rates, costs of text books and shortages of affordable learning options have increased in most schools- despite massive decrease in costs of production, dissemination and interaction. I have theorized (see my Interaction Equivalency Theory) that we can effectively substitute student-content interaction for student-teacher interaction and that is what is being done in many xMOOCs as video replaces real time lectures and tutorials. However, I also realize that “teaching presence” can be very valuable and in some cases may be indispensable. The trouble is, it is expensive and doesn’t scale well. Still though, more efforts are needed to dramatically reduce the costs of education are necessary if we are to meet the current need and the increasing demands for life-long learning on a global scale. We haven’t done a good job of helping students become self motivated and aware of their own learning style and needs and thus many have trouble learning in these type of more self directed educational modalities, but I think the promise is great enough to keep pursuing the model.

Steve: If you had to give away all your technologies, but just keep back one for personal use, what would it be?

Terry: I’m pretty addicted to my spell checker, but I think access and capacity to read and write to the global web is a very profound and critically important tool set for students, teachers and citizens - including myself!

Steve: What, in your opinion, will be the future of education?

Terry: I think that education, as a separate and formal activity that takes place in dedicated buildings will be only one small component of embedded learning that is both used for formal and informal education. In a few years we will likely smile when we think of terms like ‘e-learning’ or ‘online learning’ as being as antiquated as talking about ‘blackboard or ball point pen enhanced learning’. I hope that students will get a chance to enjoy at least once in their lives the opportunity to immerse in a face-to-face learning community, but throughout their lives they will be studying, learning with and without others as they increase their vocational, recreational, aesthetic and personal skills and knowledge. Our challenge as educators is to NOT make this a life long sentence to hard labour, but rather an enjoyable and fulfilling activity for students.

Steve: Everyone is looking forward to hearing you speak in Zagreb at the Annual EDEN Conference in June. Please give us a preview of what you will be speaking about in your keynote.

Terry: A keynote speaker rarely misses an opportunity to flog their latest book to a captive audience - even when they are giving them away as open access! Thus Olaf Zawacki Richter and I will be highlighting insights from and challenges for distance education research. In addition (if Olaf allows me the time) I’d like to talk about a second new book Teaching Crowds: Learning and Social Media that Jon Dron and I will be publishing this spring. This book introduces the ways that human aggregations of groups, networks and sets can be used and the power that collective computation provides to each.

Steve: Terry, thank you very much.

Reference

Cousin, G. (2005). Learning from cyberspace. In R. Land and S. Bayne (Eds.), Education in cyberspace, pp. 117-129. London: Routledge Falmer

The EDEN Annual Conference will take place between 10-13 June in Zagreb, Croatia. For further details, please visit the EDEN Conference website.

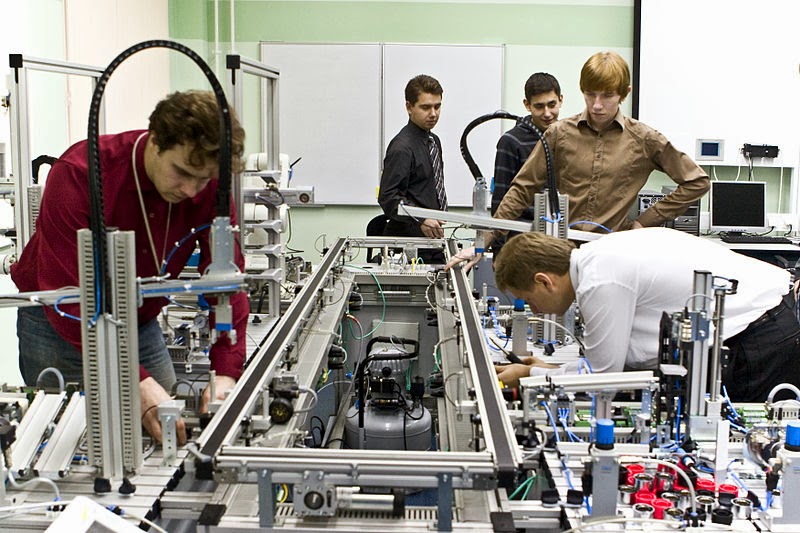

Photo courtesy of Terry Anderson/Athabasca University

Interview with Terry Anderson by

Steve Wheeler is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Ever since I read George Dvorsky's 20 crucial terms every 21st Century Futurist should know I have been thinking about one particular term he featured. His mention of the Substrate-Autonomous Person got me thinking about what possible applications should could have for education in the future. Here's a quote from the article:

Ever since I read George Dvorsky's 20 crucial terms every 21st Century Futurist should know I have been thinking about one particular term he featured. His mention of the Substrate-Autonomous Person got me thinking about what possible applications should could have for education in the future. Here's a quote from the article: