I once went on holiday to a very warm, overseas destination and deliberately left all my devices at home (except one mobile phone to be used in emergencies only). I wanted to find out if I could survive without them for two weeks. For the first day or two I thought a lot about what I might be missing online. I wondered whether people had left comments on my blog. I thought about what text messages or calls I might be missing. What would people think of me if I didn't reply? I worried about the huge backlog of emails I would have to deal with when I returned home. For the first two days, this obsessions was a little uncomfortable. Then gradually, I began to relax, and although I still thought about my online life periodically, I enjoyed my holiday, and we never had cold turkey for lunch.

Sleepless in Cyberspace? from Steve Wheeler

There are several psychological theories that can be applied to help us understand the phenomenon of computer dependency. Many of them are represented in the slideshow on this page. For example, Julian Rotter's locus of control theory may explain some of the discomfort we experience when we feel we have lost control over our online lives. Lack of access to an internet enabled device for a period of time might give you feelings of detachment from the 'flow' of the discussions and social connections you normally enjoy. When my daughter's phone was stolen, I remember her being upset to the point of feeling bereaved. She tearfully told me she had 'lost all her friends'. When I pointed out that no-one had actually died, she told me I didn't understand. All of her friends contact details were in the memory of her phone, and she felt she had lost contact with them all. She had lost control of her social life. Find out more about your own locus of control by completing this online quiz.

Another theory relating to computer dependency is Leon Festinger's cognitive dissonance theory. When you spent far more time online than you know you should - perhaps you are engrossed in an online game, and can't stop until you reach that very difficult next level - and know that you should be spending more time with your family, do you rationalise that you will 'make it up to them'? Do you make other excuses to justify the amount of time you spend online? According to Festinger, this is the result of cognitive dissonance - where a conflict of beliefs can be 'resolved' by a form of rationalisation - usually excuse making that justifies doing what you know is bad for you. Addicts and gamblers do this a lot. Smoking causes lung cancer, but although it affects other smokers, it will never happen to me. I have lost a lot of money tonight on Blackjack, but my next bet will win me back all I have lost.

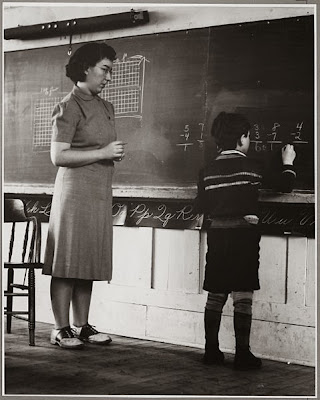

The implications of computer dependency can be quite profound. All teachers need to be aware that some children may be computer dependent, and may spend inordinate amounts of time online at home chatting or gaming when they should be getting on with their homework, or sleeping. It's a fine balance between using technology to benefit our lives, and becoming slaves to the routine and ritual of online life.

Photo by Ben Andreas Harding

Sleepless in cyberspace by Steve Wheeler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.