1) The Pedagogy or Work. Learners should be encouraged to learn through making products and providing services. This can be easily set up and conducted using Web 2.0 tools. What better way to encourage students to engage in learning any topic, than to get them to make something that represents the topics they are learning? Even better than that, how about facilitating their engagement in the commercial world? What would happen if students were encouraged to create services and products and then sell them? Several schools already do this of course. One or two keep small farms that yield produce which can be sold at market. Others support their students to develop apps or other digital stuff which can be sold online through established retailers. Students could find out about how e-commerce works by selling on E-Bay or Amazon. Social media make this process a great deal easier, but teachers of younger students should ensure that their safety is protected.

2) Enquiry Based Learning Method. Learning by asking questions is not only fun, it's effective. But we can't always get every answer right at the first attempt. Learners need to learn in a psychologically safe environment where they have permission to fail, and to learn from that failure. One of the most familiar environments for students is in game based learning. Video games, especially those that are social, and where they get to work and play within a team or guild, teach them a great number of transferable skills such as problem solving, team work, dexterity, creative thinking, negotiation of meaning, patience and persistence. Enquiry based learning too, can be incorporated into this kind of scenario, with many games posing problems and challenges for users to overcome. Students need to understand and answer the questions before they can gain more points, or proceed to the next level of the game. This is learning by stealth.

3) Co-operative Learning Method. Learners can co-operate not only in the production processes (1) and games playing (2) outline above, they can also co-operate, or even collaborate on team based creation of blogs, wikis, or video production. All of these can be created by the team, and then posted up online for a audience to appreciate, evaluate and discuss. As has been shown repeatedly in long running projects such as Quadblogging and the 100 Word Challenge, giving students an audience for their work encourages them to hone their writing skills, develop and improve their presentation skills and gain an appreciation of performing their learning for an audience. The benefits of blogging are wide ranging, and when it is developed into co-operative projects it can have a great motivational power.

4) The Natural Method. Students learn best when they are naturally interested in the topic, and this increases in success level when learning takes place in authentic and realistic contexts. Facebook and other social networking tools are great for connecting people, and most students already have an account and can use it effectively to do this. How about extending this to networking with students in other parts of the world? This would be an extension of the pen pal method used many years ago, where schools paired students with those in other schools. They then wrote to each other regularly, and learnt all about each other's cultures, backgrounds and traditions. Using social networking tools to promote e-pals could potentially spread worldwide, with students in different countries discovering about foreign lands, cultures, languages, geography, history, music and sports. See e-Pals Global for one example of how this works in schools around the world.

5) Democratic Method. Students learn about fairness, celebrating diversity, choice, friendship, relationships and a whole host of other human experiences and challenges through an appreciation of their entire community. They can take responsibility for their own choices and actions and understand how they fit into their community (local and global) through connecting with others using social media tools. Using voting tools such as Digg and organising tools such as Diigo and Delicious can aid this process, as can the like and +1 buttons of Facebook and Google Plus. Getting them to make decisions democratically enables them to understand that their opinion counts, but it must always be considered in the wider context of the community.

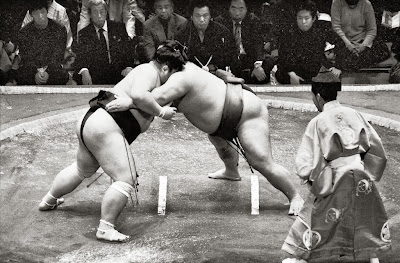

Photo by the Gates Foundation

Freinet and social media by Steve Wheeler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.